Judge thoroughly rejected ISPs’ arguments against Calif. law, transcript shows.

By John Brodkin, Mar 17, 2021 | Original Ars Technica article here.

The broadband industry’s attempt to kill California’s net neutrality law appears to have very little chance of succeeding in the US district court where the case is being heard.

On February 23, the industry’s motion for a preliminary injunction was denied by Judge John Mendez of US District Court for the Eastern District of California, as we reported at the time. We didn’t have much detail on Mendez’s reasoning last month, but we’ve since obtained a not-yet-publicly released transcript of the hearing in which he issued his verbal ruling against the injunction. (He did not issue a written ruling, citing time constraints caused by a shortage of judges in his district.)

Additional Reading

California can enforce net neutrality law, judge rules in loss for ISPs

Mendez’s denial of the injunction means that California can enforce its net neutrality law while the case continues, leaving open the possibility that Mendez could ultimately side with the broadband industry. But Mendez explained during the hearing why he thinks the industry is unlikely to succeed at trial.

“I don’t find that the plaintiffs have demonstrated a likelihood of success on the merits at this stage of the litigation,” Mendez said.

The California law prohibits Internet service providers from blocking or throttling lawful traffic. It also prohibits requiring fees from websites or online services to deliver or prioritize their traffic to consumers, bans paid data cap exemptions (so-called “zero-rating”), and says that ISPs may not attempt to evade net neutrality protections by slowing down traffic at network interconnection points.

AT&T stops charging for zero-rating

Mendez’s ruling is already having an effect, as AT&T announced Wednesday that it will end its “sponsored data” program in which it charges online services for data cap exemptions.

AT&T said:

“We regret the inconvenience to customers caused by California’s new ‘net neutrality’ law,” “Given that the Internet does not recognize state borders, the new law not only ends our ability to offer California customers such free data services but also similarly impacts our customers in states beyond California.”

As Stanford professor Barbara van Schewick pointed out, AT&T’s claim that California’s zero-rating ban forces it to end sponsored data in other states is contradicted by the fact that AT&T lets customers opt out of sponsored data. Since AT&T has already implemented the ability to disable sponsored data for individual customers, it could comply with the California law simply by turning the feature off for all customers in California.

Ernesto Falcon, senior legislative counsel for the Electronic Frontier Foundation, wrote on Twitter that “AT&T’s version of zero rating with low data caps was a way to drive their users to content they owned. It is why low-income advocates in CA wanted it gone. Mobile-only users tended to be low-income and weren’t getting the full Internet.”

AT&T also complained that a “patchwork of state regulations” is “unworkable,” failing to mention that AT&T’s longtime fight against US-wide net neutrality rules helped ensure that states would issue their own laws.

Judge didn’t buy ISPs’ interstate argument

Most of the court hearing transcript consists of the judge asking questions to each side, and he had many more skeptical questions for broadband-industry lawyers than he had for California. His skepticism carried over from the arguments phase of the hearing to the part where he announced and explained his decision.

The industry, represented by lobby groups for the major cable, DSL, fiber, and mobile Internet providers, “have asserted that the Communications Act gave the FCC the exclusive authority to regulate interstate communications, leaving the states only able to regulate purely intrastate communications,” Mendez said. “But the court finds that the provisions of the Act that the plaintiffs rely on do not support the arguments that have been raised.”

For example, Section 152 of the Communications Act “grants the FCC the authority to regulate interstate communications while precluding it from regulating intrastate communications, but this grant of authority to the FCC indicates nothing about the power of the states,” Mendez said. The fact that US communications law “specifically left out certain types of interstate communications from the FCC’s jurisdiction, like information services, indicates to this court that this is not the type of pervasive regulatory system that left no room for state law,” he said.

Under former Chairman Ajit Pai, the FCC reclassified broadband as an information service instead of as a telecommunications service, abandoning the Title II power the FCC has to regulate ISPs as common carriers. Pai’s FCC also claimed that state net neutrality laws must be preempted because they would conflict with a federal policy of non-regulation.

In the California case, the ISPs “argue that the state common carrier regulations of information services would stand as an obstacle to Congress’s decision to immunize these services from such regulation,” Mendez said. But Congress did not clearly state any intention to preclude both state and federal regulation of information services, he said. Mendez then cited a section of Congress’s 1996 update to the Communications Act that says, “This act and the amendments made by this Act shall not be construed to modify, impair or supercede federal, state, or local law unless expressly so provided in such Act or amendment.”

Precedent Cited By ISPs Not Relevant

Mendez also addressed the ISPs’ argument “that the Supreme Court has long held in analogous contexts that where Congress has prohibited federal regulators from imposing specific obligations, the states may not impose such regulation without running afoul of the Supremacy Clause.”

The ISPs’ argument relies primarily on a 1986 ruling in a case involving federal regulation of wholesale natural gas in interstate commerce, Mendez said. But that case, in which the federal law “occupied the field and precluded state regulation… was a straightforward application of field preemption that has no application here,” Mendez said.

Pai’s FCC Decided it “Lacked authority”

Mendez also criticized the ISPs’ argument that the California law conflicts with “the FCC’s deregulatory policy for broadband Internet access” that was spelled out in Pai’s repeal of net neutrality rules. As Mendez said, the Pai FCC’s “order reinterpreted broadband Internet as an information service covered by Title I of the Communications Act rather than as a telecommunications service covered by Title II and, thereby, placed it outside the FCC’s regulatory ambit.”

Mendez continued:

The upshot is that the [FCC’s net neutrality repeal] order is not an instance of affirmative deregulation but, rather, a decision by the FCC that it lacked authority to regulate in the first place… [A]gency regulations may preempt state law only if the agency has delegated authority over the subject matter. An agency’s failure to regulate a practice it lacks the authority to regulate simply shows that it is respecting the limits of its powers, it’s not exercising delegated authority to decide whether the matter should be free from state regulation as well.

The FCC does have authority to decide whether broadband Internet access is an information service, but Mendez said that “the deregulatory purposes behind that decision do not have preemptive effect.”

This is similar to what a federal appeals court ruled in 2019 when it upheld Pai’s repeal of federal net neutrality rules while blocking a nationwide preemption of state regulation. “[I]n any area where the Commission lacks the authority to regulate, it equally lacks the power to preempt state law,” that ruling said. Despite blocking Pai’s attempt at a nationwide preemption, the 2019 ruling said that individual state laws could be challenged on a case-by-case basis, allowing litigation against California to continue.

After Biden replaced Trump as president, the US Department of Justice dropped its own lawsuit against California, so the ISPs are fighting on without federal support.

Zero-Rating Ban is Not Rate Regulation

The transcript also shows that Mendez disagreed with the broadband industry over California’s ban on ISPs charging online services for “zero-rating,” the practice in which AT&T and other carriers exempt specific services from counting against data caps. The ISPs argued that the “zero-rating provisions improperly regulate the rates charged,” Mendez said. He refuted that argument, explaining:

The zero-rating provision provides that as with paid prioritization, mobile broadband providers cannot manipulate their subscriber’s Internet access experience to favor paid or affiliated content over other content on the Internet.

But as defendants points out, these provisions do not regulate how much providers can charge their customers because providers can charge the user as much or as little as they like for the service and, thus, there is no conflict with the [Communications] Act.

Preventing Harm to Internet Users

Having thoroughly disputed the ISPs’ arguments, Mendez said that denying the injunction would not cause irreversible harm to the industry. “Finding that there is no likelihood of success on the merits of the arguments raised, the court similarly finds that there is, then, no irreparable harm [to ISPs],” Mendez said.

California and its supporters filed briefs “describ[ing] in great detail how the regulations are essential for fair access to the Internet,” Mendez said. He continued:

These are not hypothetical concerns. For example, the defendant submitted a declaration by Anthony Bowden, fire chief for Santa Clara County, that describes how Verizon allegedly throttled the fire department’s connection in the midst of their response to the Mendocino Complex Fire.

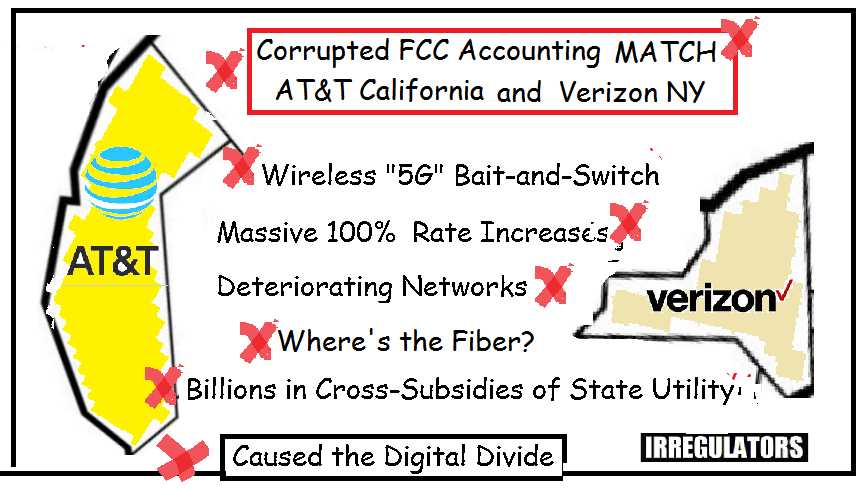

Defendants also submitted comments from the New York attorney general, who found that large ISPs made the deliberate business decision to let their network connections become congested with traffic and used that congestion as leverage to extract payments from others.

It does appear… that issuing an injunction would negatively impact the State of California more than the ISP companies and over the well-being of the public. It is clearly not, the court finds, in the public interest to issue the injunction and the balance of equities, the court finds, weighs in California’s favor.

As ISPs Appeal, Judge Urges Congress to Act

The ISPs’ lobby groups are appealing Mendez’s denial of the injunction to the US Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. The lobby groups would also likely file an appeal if Mendez rules against them after the case is heard in full.

Mendez, who was nominated by President Bush in 2008, said that “there is an elephant in the room. There is clearly a political overtone to this case.” Mendez said his ruling against ISPs “is a legal decision and it should not be viewed through any type of political lens… it’s obvious to all of us that this case raises issues that, quite frankly, might be better resolved by Congress rather than the federal courts.”